Written by Lauren Dulude, MS, CCLS for Child Life Disaster Relief

The COVID-19 pandemic has taken its toll on individuals in a variety of ways; as healthcare professionals on the frontlines, we have witnessed the negative effects of this pandemic firsthand. Local, national, and worldwide health organizations have shared best practices with us regarding self-care, explaining COVID-19 to children, maintaining consistent routines, and practicing hand hygiene and social distancing. With vaccination rates rising and the Center for Disease Control (CDC) and Food and Drug Administration recommending vaccination to be rolled out to people as young as 12 years of age, it is time to shift the conversation. By arming healthcare professionals with core concepts of comfort during pediatric procedures, we can lessen the likelihood that widespread childhood trauma from vaccination is not yet another negative effect of this pandemic.

The first step to mitigating trauma is to prepare children prior to the procedure. Using clear, honest, and developmentally-appropriate language helps children understand the procedure and feel included in their care (Lambert, et al., 2013). Children identify the importance of knowing chronological steps of the procedure, sensory information, and their options for coping (Bray, et al., 2019). In addition, the likelihood of having to restrain children for the procedure diminishes when more choices and opportunities for preparation are provided (Folkes, 2005). Most desirable, however, would be the utilization of comfort positioning provided by the caregiver or a healthcare professional.

The CDC (2019) supports comfort positioning during vaccinations as they aid in comforting children, provide a safe, non-threatening hold, and allow caregivers to nurture and comfort their children in stressful situations. Comfort holds and caregiver presence during painful procedures can be beneficial to both the child and caregiver, lowering both of their anxiety levels (Waseem & Ryan, 2003). An additional coping tool that can be utilized is distraction, which Koller and Goldman (2012) suggest is most beneficial when concentrated on deep breathing, guided imagery, developmentally-appropriate games, or interactive toys.

In any case, preparation, comfort holds, caregiver presence, and distraction are powerful tools that lead to pediatric coping success, specifically for vaccinations. In a recent Policy Statement released by the American Academy of Pediatrics (2021), they recommend certified child life specialists (CCLS) provide education to medical teams to uphold developmentally-appropriate care and family-centered care. Therefore, in order to lower the risk of developing vaccination-related trauma for patients and caregivers, a foundation grounded in these key child life components is essential to the overall well-being of patients and families.

References:

Bray L, Appleton V, & Sharpe A. (2019). The information needs of children having clinical procedures in hospital: Will it hurt? Will I feel scared? What can I do to stay calm? Child Care Health Dev., 45(5), 737-743. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12692

Center for Disease Control. (2019, August 5). How to hold your child during vaccination. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/parents/visit/holds-factsheet.html

Folkes, K. (2005, July). Is restraint a form of abuse? Kathryn Folkes questions nurses’ acceptance of the routine use of restraint during clinical procedures. Pediatric Nursing, 17(6).

https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A134382230/HRCA?u=mlin_b_childh&sid=HRCA&xid=82 a979b9

Koller, D., & Goldman, R. (2012). Distraction techniques for children undergoing procedures: A critical review of pediatric research. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 27, 652-681.https://www.pediatricnursing.org/article/S0882-5963(11)00575-6/pdf

Lambert, V., Glacken, M., & McCarron, M. (2013). Meeting the information needs of children in hospital. Journal of Child Health Care, 17(4), 338–353.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1367493512462155

Romito, B., Jewell, J., Jackson, M., AAP Committee on Hospital Care, & Association of Child Life Professionals. (2021, January). Child Life Services. American Academy of Pediatrics, 147 (1). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-040261

Waseem, M., & Ryan, M. (2003). Parental presence during invasive procedures in children: What is the physician’s perspective? Southern Medical Journal, 96(9).

https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A109738903/HRCA?u=mlin_b_childh&sid=HRCA&xid=34 8d3ad0

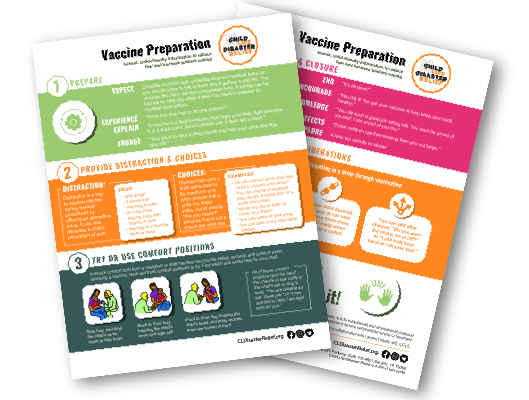

Vaccine Tip Sheet

Developmentally appropriate preparation and intervention before, during and after medical procedures has been shown to reduce emotional distress and fear, and increase positive coping in children.

Poster SET

2 pages formatted for standard 8.5 x 11″ paper